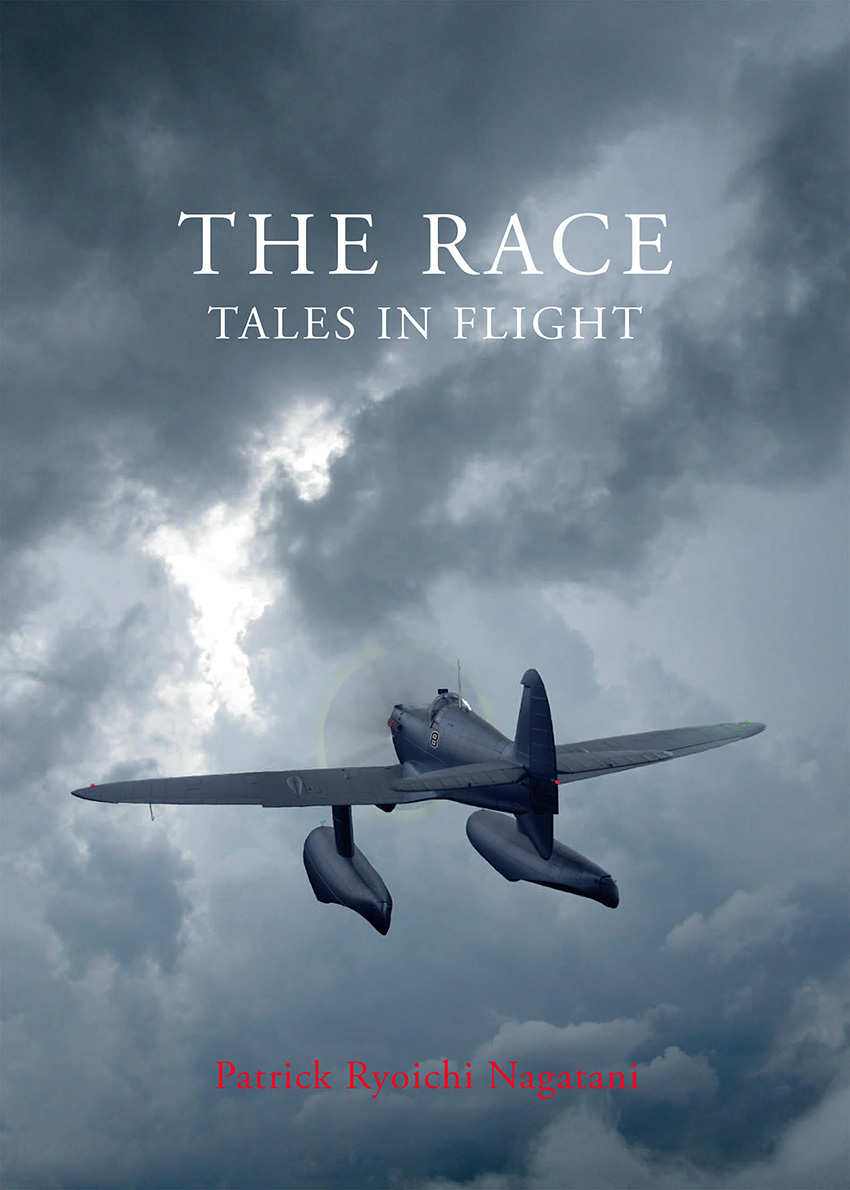

the race: tales in flight

Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani

In collaboration with Marie Acosta, Kristin Barendsen, Felissia Cappelleti, Christine Chin, Randi Ganulin, Feroza Jussawalla, Nancy Matsumoto, Dolores Richardone, Andre Ruesch, Ulrike Rylance, Julie Shigekuni

Albuquerque Museum and SF Design, llc / Fresco Books, 2017

Review by Lauren Greenwald

Issue 104

The Race begins with a search.

A search for thirty-six Supermarine Spitfire airplanes rumored to have been buried in Burma at the end of World War II. The subsequent discovery and unearthing of those planes sets the stage for Patrick Nagatani’s novel, The Race: Tales In Flight.

The story’s protagonist is Keiko Kobahashi, CEO of Mitsubishi Corporation, who devises and executes a grand plan. Fifteen of the exhumed planes are acquired and transported to Tokyo, where they are redesigned and reborn as state-of-the-art floatplanes, intended for a trans-Pacific (Tokyo to San Francisco) air race. Fifteen pilots are carefully selected, individuals of all ages and from all walks of life – a disrobed Tibetan Buddhist nun, a housewife, former and current military pilots, and an aspiring astronaut, to name a few. They are all women.

The story is told from the point of view of the pilots – each one is given a chapter, and each chapter takes place during their flight across the Pacific. These fifteen chapters are supplemented by only three other chapters, which provide the framework of the narrative. The Prologue and Training chapters give a brief pre-history and introduce the characters, and the Epilogue, of course, gives is the after-race details. It’s interesting to note that the Prologue, Training, and Epilogue chapters are written, not from the point of view of one character (not even of Keiko, the architect of the event) but of the group – a collective, inclusive “we.”

In the solitude of the cockpit, however, we find only the individual characters and their thoughts. They have a set flight plan, with three refueling stops breaking up the more than 5,000 nautical mile journey. As each woman’s journey progresses, her story unfolds, and each chapter is a glimpse into another’s world. We are privy to history, memories, hopes, and dreams. Cultural, religious, and ideological identities are examined and even questioned, as the characters consider their own lives and those of their fellow pilots. The various challenges they have faced in their lives – regret, betrayal, abandonment, sickness, and death – surface. For some, there are daydreams and hallucinations. For all, there is a reckoning, and catharsis.

In addition to the refueling stops, there are two “landmarks” of sorts along the path. The first is the Great Pacific garbage patch. An ecological disaster of mammoth proportions, it’s a potent symbol for the current state of our planet. As I read the book, I began to see this as a classic hero’s test or a trial, one she must pass before moving on to the next level or phase of existence. It was interesting to see how the characters responded to this trial – which ones chose reduce altitude to get a look at the monster in the Pacific, risking an increase in flight time, and which ones stayed their course. And like many trials, at least those in real life, upon completion there were no showers of reward or lightning strikes of transformation, just a moment of increased awareness. The second landmark occurs at the end of the journey, when all pilots are instructed, on approaching San Francisco, to “descend to 7,890 feet and go through the uppermost cloud, which is known as Cloud Nine.” I loved the idea of each pilot passing through a physical “Cloud Nine” while also experiencing that state of euphoric exaltation, as we more commonly know it.

The Race is a tale of epic adventure. Flight represents freedom, and tales of flight are often filled with romance and allure. In focusing on each pilot’s journey, this book reminds me of the many great books written by flyers about flying. Some of these are even referenced in the chapter of the character Ayame Kobahashi – Champagne 2, as inspiration; West with the Night by Beryl Markham, a memoir of her time as a bush pilot in Kenya, and Wind, Sand and Stars by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, chronicling his years flying mail routes across the Sahara and in South America. These books are transformative; for anyone who has longed to escape the here and now for a far-away place, they are incredibly potent – a glimpse into the unknown. The flights – long, arduous, solitary passages – are vehicles for escape, adventure, and self-discovery. I’m reminded as well of two other books in my personal pantheon of favorites, Blue Highways by William Least Heat-Moon, and The Long Way, by Bernard Moitessier, which follow the voyage/memoir model of Markham and Saint-Exupéry, but by land and by sea, respectively. I see a particular connection to The Long Way, a memoir of Moitessier’s participation in the first solo around-the-world sailboat race. Alone for weeks on his sailboat, he reflects upon and revises his philosophy on life, questions our place in the world, and our attendant responsibilities. In the home stretch of his race, just before rounding Cape Horn to sail north to Great Britain and the finish line, Moitessier decides to turn around, to abandon the race, and return to Tahiti. He no longer cares about winning, for him, the race has served its purpose. The final character in The Race, Arianne Maya Parker, flying Ochre 15, makes a similar choice. Instead of completing the race in San Francisco and joining her cohort, she continues north, returning to her home and her family.

For me, the magic of this book is in the telling of each journey. Particularly, the way a long, solitary trip serves to focus your thoughts to an extreme degree. The hours spent alone in your own head, skipping from past to present to future, bouncing wildly between ideas, frame a space in which a special clarity can be achieved. This is a phenomenon I’ve been trying for some time, unsuccessfully, to articulate in my own work. But here, in the cumulative stories of the pilots, and the richness of detail in their inner monologues, this elusive space is beautifully communicated. And the metaphor of the sky as a space of renewal and transformation is described, in a wonderful passage in the Prologue, “For us, the sky is the source of light, moisture, and energy. It illuminates and reflects the sea. Both three-dimensional and two-dimensional, it is a place with many places in it. Thin yet deep, near yet far–always the same, yet always new.”

This new-ness is important to me. I consider the life of an artist to be one in which we are continually seeking the new – always learning, always growing, and finding ways in which to express that which we hold most dear. As I read this book, it was difficult to separate what I know of the artist and his career from my interpretation of it. For readers who don’t know anything about Patrick Nagatani, it can be read as a fun, female-driven adventure, a multivalent travelogue coupled with a larger meditation on, among other things, “the human condition and the universal need for compassion.” I think this philosophy is wonderfully summed up in a description of Keiko: “Her empathy signified innovation and sensitivity to others, which was a huge catalyst for creativity.”

The idea of creativity is another important point. For those familiar with Nagatani’s legacy, the book is like an illustrated field guide to the creative process, a map for artistic renewal and development. Knowledge of his past projects fosters flashes of recognition as small details from his many areas of interest emerge. For many artists, the reading of a work of art becomes fuller and richer with some knowledge of the working process, be it conceptual or technical. And it’s taken for granted that our lives and our experiences are driving forces in the work we make. There’s a certain suspension of disbelief when you read a novel. You take everything as fact, in a way. For those of us with some knowledge of Nagatani’s life and work, the elements and characters we recognize become little treasures to find in the narrative and interrupt this disbelief – but in a good way, pulling the curtain back from what we imagine his creative process to be. The question of what is real or not real becomes irrelevant. Fittingly, his alter ego from an earlier project, Ryoichi, the Japanese archaeologist, is one of the few central male characters. The Ryoichi project, which Nagatani worked on from 1985–2001, involves archaeological excavations unearthing, among other things, luxury automobiles buried at ancient sites. The coincidence of the buried Spitfires at the center of this project is a delightfully fantastic one. Other “real” things are there – the characters of Dr. Kazuhiko Watase, the acupuncturist, and Annie, the faithful dog, the practice of Chromotherapy, and the harrowing particulars of a cancer survivor’s condition as described in the story of Nanibah Jackson (Yellow 13), a young Navaho/Laguna woman from New Mexico. Sid the stoma even makes an appearance. The process of creating this new world must have been a challenging, but also extremely rewarding one, and it occurred to me that it’s not so different from any visual project Nagatani constructed in the past.

Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani’s career was long and renowned, both as an internationally acclaimed photographer and an educator. His art investigated the concept of ‘photographic fact’, and his many projects revolved around imagined tales, stories, and manufactured flights of fancy. In an interview from several years ago, he said, “Photography always supposes the truth. My sensibility has always been that photographs lie, they tell stories. Fiction has always existed.” He goes on to say, “My favorite part of fiction is that it is established from truth. For me, everything is true.”

His approach to art-making was conceptual and directorial, and he had several long-term collaborative projects with other artists. This project is no exception. He first conceived of the novel eight years ago, and while he wrote six of the chapters and contributed to several more, he reached out to other artists and writers to join him in the journey. In the early stages of the project, he approached it from his past experience as a visual storyteller. He built models for all of the planes, painted them, arranged, lit, and photographed them, and using over 2,000 photographs of the sky from his friend and fellow photographer Scott Rankin, he began constructing the photographs to be used in the book. In a 2014 discussion at SITE Santa Fe with the writer Lucy Lippard, he talked about his decision to tackle a novel. He said, “I’m known as an artist who reconstructs himself constantly… I follow what’s interesting to me. What seemed to be really challenging was to write.” He later elaborated, “I started thinking about narrative, and about how words fulfill the story ... I’ve read most of my life and a lot of my work comes from reading fiction and non-fiction, and I saw that as a great challenge, to present these ideas that I had represented in the fifteen pilots.” On the decision to have an all-woman cast of characters, he noted, “The novel is really about looking back to early centuries about when witches ruled the world, and about how that power was taken from them by men.” He joked about the perceived strangeness of writing a book from the female perspective, as a Japanese-American male, but went on to say, “I don’t call it a feminist book, I just think it’s a book on reality.”

I wanted to know more about the making of the book, and was able to speak with André Ruesch, who wrote the chapter for the character Leah Katzenberg – White 6. He is a former graduate student of Patrick’s, and the only other male to contribute to the book. His take on the use of women as the main characters is a reflection on Patrick’s view of women as being “more suited to changing the world.” What if we really could change the world? Another profound element in the plot of The Race is the resolution of Keiko’s master plan. With her great personal wealth and power, she has built a complex in Hawaii named Shinatobe, for the Japanese Goddess of the Wind. Her goal is to bring as many of the exceptional women she had chosen for the race to live and work there, if they so choose, to share their many skills and have carte blanche to develop their ideas. The desire, above all, is to empower women, to bring them back to making the decisions, and to help save the world. The Hawaii compound is the ideal model of how can we live – all part of a greater collective, if we can only be allowed the freedom and support to achieve it.

André and I spoke for some time about the process of collaborating on the book, and he speculated that in the beginning stages of the project, Patrick may have started writing and realized the work needed the authenticity of other voices – and in his generous spirit, he “offered up a stage or platform for others to interact with him upon it.” When I asked him about how they were introduced to the project, he told me that each contributor was sent the prologue, and asked to choose their character’s name, nationality, the color and number of the plane, and so forth. There were very few instructions per se – it was stated that every character experiences catharsis, but the what, how, and why was left up to the individual writers. Having known Patrick as a teacher, he was familiar with his effectiveness as a planner, and his gentle method of direction. When I commented on the coherence in writing style – the book does not read like it has multiple authors – he said that instead of manipulating the writers into a certain frame of mind, Patrick created a setting, in which “the genius was in the specificity of instruction on one hand and the subsequent lack thereof." This worked particularly well in the multigenerational arc of the stories. Ideas get worked out over generations – we are not just the sum of our experiences, but also those of our parents and their parents. Patrick set the stage by beginning the story at WWII and ending it in the present. In working with this decades long timeline the writers were forced to grapple with their own personal histories and to consider the totality of multiple generations. André made another observation that I thought was particularly poignant – he said that writing the book reinforced, for him, the appeal of fiction – you have the freedom to imagine another version of you – in another body and gender, but also in another reality, one in which perhaps you have the opportunity to change things.

This made me think of another observation I had when first reading the book - it is a meditation on mortality. I couldn’t help but think of the stories as an analogy for examining one’s life in a more profound manner, as we do when we face the death of a loved one, or our own impending death. Crossing the ocean, navigating its challenges, and finally descending through Cloud Nine is a pretty effective metaphor for passing between planes of existence. Could the compound in Hawaii also represent a metaphysical realm, one in which you have the opportunity to be the best person you can be, free of restraints, without the necessity to sacrifice your previous life?

While this book was years in the making, like many long-term projects, the final stages were completed very quickly. Michele Penhall, former curator of prints and photographs at the University of New Mexico Art Museum and a longtime friend of Patrick Nagatani’s, edited the final manuscript. Penhall collaborated with Nagatani on the 2010 monograph and retrospective exhibition, “Desire for Magic”, and in a recent conversation, she told me a little about the final push towards publication. They chose to work with Kay Fowler and Nancy Stem of Fresco Books, and began the publishing process in the spring of this year. The books were delivered in October. Penhall describes Nagatani as an incredible craftsman and consummate planner - his very organized, directorial mode of working made it possible to get the book completed on such a compressed timeline. He was involved every step of the way, even choosing the paper for the book. Penhall said, “Like all of his work, I consider this a conceptual art project and it needed to be done well. Patrick loved beauty and we all wanted his last endeavour to be a beautiful object.”

I think she describes the book best, as she wrote to me in a later email, “Patrick’s art always involved a story, and it is always beautiful. And he dealt with social issues within his stories, but generally in a subtle way. The Race seems to me to be his last challenge as an artist—to take on a new method of working i.e. writing—and his last gift to his audience. This was his last definitive word on so many personal and social issues he cared deeply about—animals, the environment and human intervention in our landscape, and our post-nuclear world.”

Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani died on October 27, 2017, at the age of 72. He lived to see his last project completed, and to host a book signing at the Albuquerque Museum the week before his death. For the many people who came out that night to celebrate him, he graciously and cheerfully signed book after book. In his typical kind and generous manner, he personalized every one. In his life, he was beloved and admired by so many, but his legacy of creativity and generosity lives on in the work he leaves behind, and in the memories of those who knew him. He will be missed.

LEAH KATZENBERG – White 6

RAYA SOL DEL MUNDO – Copper 4

PICCOLA UCCELLO – Chartreuse 14

AYAME KOBAHASHI – Champagne 2

FIROOZEH IRANI – Turquoise 10

Lauren Greenwald iss an Assistant Professor of Photography at the University of South Carolina.

She lives and works in Columbia, SC.