Ballenesque – Roger Ballen: A retrospective

By Roger Ballen with an introduction by Robert J.C. Young

Thames and Hudson, 2017

Review by Leo Hsu

Issue 110

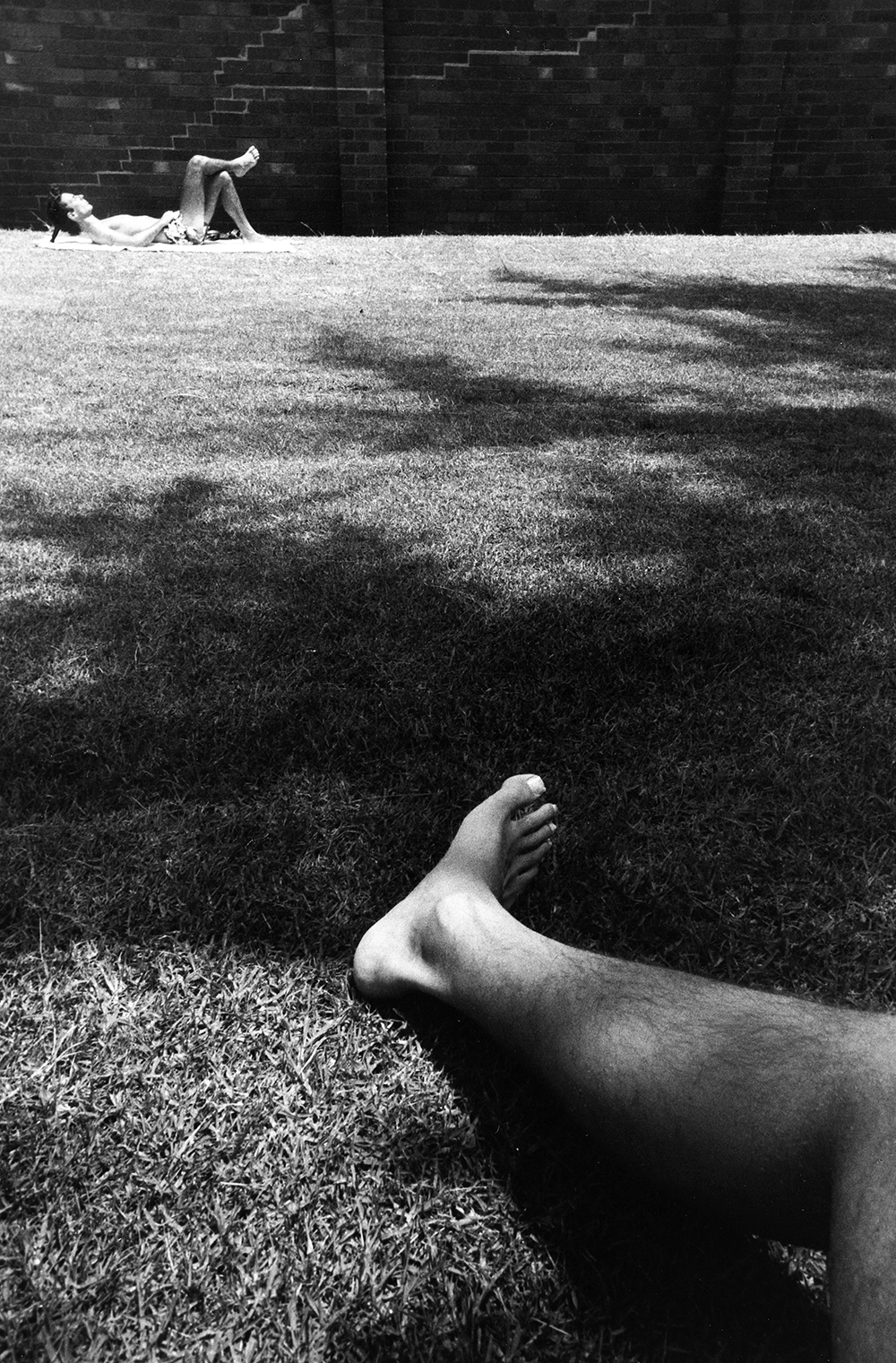

Roger Ballen’s mysterious, often unsettling images defy interpretation and yet confidently adhere to their own narrative logics. Ballen’s photographs play on the psychological tension between a disturbance of norms and the proposition that these disturbances are no less legitimate than the viewer’s own sense of normal. Ballenesque - Roger Ballen: A Retrospective provides a sweeping view of the artist’s career, beginning with his earliest travel photographs made after graduating from Berkeley in 1972, and moving through his many well-known projects including Platteland, Outland, and Boarding House, to his 2016 Theatre of Apparitions, and beyond. Texts in the book illuminate Ballen’s personal history and working methods; with the images, the reader can see how each project lead from one to the next, how Ballen moved into increasingly interior spaces and later into an erasure of human faces in his stylized photographic descriptions of psychological spaces, and how Ballen’s ideas about theater and photography articulate with one another as defining aspects of his work. The book is a view on Ballen’s mind from within Ballen’s mind, an extended interview between Ballen and himself.

Twirling Wires, 2001

Visually, Ballenesque persuasively describes a progression over decades. The settings in which images are made are increasingly constructed; lines, in the form of wire, graffiti, and in painting and drawing, become an ever more significant element; spaces become more claustrophobic. Figures, both photographed and hand-illustrated, signal “primitive” motifs and the collapse of convention in the face of uncontrolled impulses. Ballen seeks to reveal something about human nature that feels basic and dangerous, oriented towards immediacy and the loss of certain aspects of the self.

Textually, in five reflections by Ballen and an introduction by Robert J.C. Young, a case is made for the continuities within Ballen’s progressions. There is a continuity of interest in theatrical performance influenced by Samuel Beckett and the “Theater of the Absurd,” and there is continuity in specific ideas about photography that inform even Ballen’s most otherworldly work. Ballen’s voice dominates the book in both words and pictures, discussing his processes, influences, and aims, and yet the pictures are no less startling after we have been offered a look behind the curtain.

It’s been some time since Ballen has been a documentary photographer by any conventional definition and even his controversial Platteland, in which he portrayed the precarious marginality of poor whites under apartheid – barely surviving and often mentally ill and living with superstition – appears to have been intended as a kind of visual storytelling. The book includes a contact sheet from his best-known image, “Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transvaal, 1993” and Ballen describes coming upon Dresie while driving past his garden and then realizing that Dresie had a twin brother. It’s jarring and delightful to see the twins grinning cheerfully in outtakes, two frames after the image that we have come to know. They come across as acting, putting on a serious face for Ballen. The story that Ballen chooses to tell with his selection here, as with much of his work, is one that feels confrontational, even menacing, where the twins appear to be staring back at us, the audience. This is what Ballen has been doing since then, making pictures that stare back at us and seek to make us uncomfortable, where the images describe a stage; the people - as much as the wire, the cages, the birds, the graffiti on the walls - are players and props.

In Young’s introduction, and in Ballen’s own texts, Ballen’s photographic influences are laid out:

I owe to Kertész the understanding of enigma, the quixotic, and formal complexity that underlies much of my work… Among other photographers who have influenced me are Henri Cartier-Bresson (the decisive moment), Elliott Erwitt (the humorous and the absurd) and Ralph Eugene Meatyard (the psychological). (13)

Ballen’s invocation of Cartier-Bresson, who is known for his engagement with the world through which he moves and in which he seeks meaning, is particularly notable. Unlike these photographers of the street and of the world, Ballen has created the environments in which his mind’s eye can seek alignment within a psychological stage setting. Ballen in his own terms recapitulates Cartier-Bresson’s “The Decisive Moment”:

In the places I work in, there is always a lot of activity; there is movement all the time. Objects and drawings are being put up and taken down; people are coming in and out; birds are flying around; animals are crawling along the door. It’s then my responsibility, and no one else’s, to recognize the exact moment when the picture should be taken. It is my job to perceive the flux as it moves from one place to the next.

At a certain moment in time, unity, life, intensity and poetry come about, and it’s my job to know that point. To find it, I have to rely on various parts of my mind. We commonly divide the mind into the conscious and the subconscious, but that’s the easy way of talking about it. In reality, there is an internal force – a being that is outside the control of consciousness, working on so many different levels – that makes the final decision. There is a moment when this decision-maker, to give it a name, changes from a red light to a yellow light. Then I walk to my camera, pick it up, and start to get it ready. But I don’t press the shutter until I get a green light and hear ‘Go, go!’ But what tells this decision-maker to say ‘go’? I’m not sure I have an answer to that question. (331)

From Outland onwards, Ballen has created absurd and surreal environments in which to exercise the decisive moment, worlds created in part by his unconscious mind that are then analyzed by his conscious and unconscious mind for meaning. It’s this feedback loop that makes the images more dynamic than any completely planned tableaux, and more surreal than observational photography.

All surrealism requires a realism to subvert, however, and it’s another photographic characteristic - the belief in a photograph as a faithful record - that gives Ballen’s work a feeling of authority. The audience acknowledges that what we see has existed in the world and stood before the camera, and we are forced to reckon with Ballen’s constructions as possible facts. In the specificity of the photograph is embedded detail- a gesture, a look in someone’s eyes, the way flesh appears over bone, the fur on a dog or the feathers on a bird’s wing as it flies, that can potentially act as a punctum. “[For] me,” Ballen writes, “a photograph has to feel as though it could never occur again. It has to express an authentic, unrepeatable moment. Usually, the more that people believe in the authenticity of this moment, the more impact, all things being equal, the picture has.”

***

Young lays out the qualities of the “Ballenesque,” which he describes as a style that is so distinctive that even work by another person in this style would be identified with Ballen. Young finds four characteristics of the “Ballenesque”: “prehensile portraits” where subjects’ “expressions and physiques emphasize physical distortions that simultaneously suggest forms of psychic disturbance”; “aleatory assemblages” – a combination of human and animal subjects in surprising and “unfathomable” juxtapositions; “windowless walls”, often with wire, often covered in writing or drawing, a flat backdrop against which action is played out; and “dark junctures of disjuncture,” abstractions and symbols that place us in an inscrutable and often despondent alternate reality. Together these thematic and affective descriptions cover much of Ballen’s work. (8-11)

However, “Ballenesque” is a term of Ballen’s own creation, and, unlike Young, he intends it to describe his own work, not the possibility of others’ emulation of it. (259) The aim of Ballenesque seems to be to solidify Ballen’s work as a unified project but I wonder if calling attention to some of his deviations, or even reading his work as exploratory in its direction rather than assuredly inevitable, would have illuminated the work’s possibilities. Young’s essay notwithstanding, there is little external perspective on Ballen’s work here (except for his own quotations of passages others have written for his catalogs), no address of criticisms surrounding his portrayal of marginalized subjects, and really no attempt to put Ballen in relation to other creators apart from his collaborators.

It is extraordinary that Roger Ballen has worked with and has been driven by the same kinds of themes – the tension between chaos and order, the creation or work as a psychological self-examination - in so many different iterations. And yet, while Ballenesque shows us the lines along which Roger Ballen’s work has evolved over time, it does not show us how Ballen’s work at each stage has allowed him to resolve and redirect his own questions. I would have liked to have read an essay that explored the stated influences of R.D. Laing, or Art Brut, or Beckett, or Cartier-Bresson on Ballen, all of which are discussed briefly but none of which are explored in depth. How did Ballen understand these influences and how were they important to him? Or an examination of the unsure edges of the work - were there ever mistakes or dead ends, and what was at stake in Ballen’s decisions? For work that deals with the messiness of the human psyche, Ballenesque is surprisingly neat, confidently streamlining a clearly complex body of work. The artist has a lot to say but the monologic nature of the book leaves me hungry for outside perspectives that would allow us to consider Ballen as author rather than as his own interlocutor. Admittedly, this kind of an interpretive approach searching for meaning would be akin to a psychological analysis, precisely the kind of thing that Ballen in his work has eschewed.

My Leg, South Africa, 1974

Dresie and Casie, Twins, Western Transvaal, 1993

Die Antwoord, 2008

Take Off, 2012

Family Room, 2014