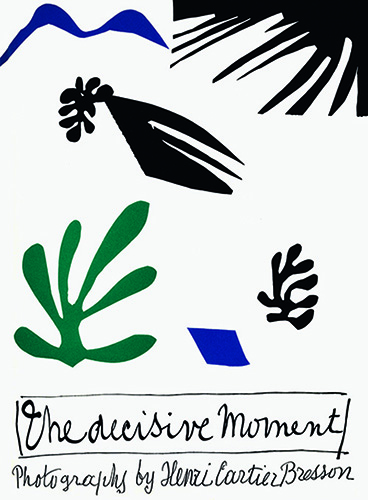

The Decisive Moment

Henri Cartier-Bresson

with an essay by Clément Chéroux

Steidl 2014

Reviewed by Leo Hsu

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.

- Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Foreword,” The Decisive Moment

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s best-known photograph may be the 1932 image of a man jumping over a puddle behind the Gare St. Lazare. The meaning of “decisive moment” seems self-evident from this picture: the timing, the composition, the totality of the picture, an ordinary moment transcribed as a complete statement. It is at once obvious and marvelous, an act of description and a small revelation. But since The Decisive Moment’s original publication in 1952, the phrase “the decisive moment” has taken on a life of its own. Indeed, this phrase may be better known than any single photograph by Cartier-Bresson.

Place de l'Europe, Paris, 1932 (also known as "Behind The Gare St Lazare"). © The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson, published by Steidl www.steidl.de

The moments described in Cartier-Bresson’s pictures are not all as fleeting as the one photographed in this image. Many of the photographer’s images are much slower. Cartier-Bresson’s moments include not only the dynamic coordination of form, but also acts of looking that consider gesture, expression and a transient connection with his subjects. Paradoxically, the popularity of the term “decisive moment” may have done Cartier-Bresson a form of disservice; while his individual photographs are very much about the “simultaneous recognition” of significance and form, there is more to his photography, as it related to life – his life, and human life – than individual pictures.

Cartier-Bresson writes in the book foreword as a photojournalist, describing photography as an act of investigation, and allows that a picture-story, using multiple photographs, may be the most effective way to communicate all that the photographer wants to say. As with individual pictures, so with a group: Cartier-Bresson tells us that the investigation is “the joint operation of the eye, the brain, and the heart”. The investigation, however, is an ongoing process. Decisive moments punctuate, but the important thing, for Cartier-Bresson, is for the photographer to have a persistent engagement with the world. Here is what follows the famous quote above:

I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us, which can mold us, but which can also be affected by us. A balance must be established between these two worlds—the one inside us and the one outside us. As the result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come to form a single one. And it is this world that we must communicate.

Here are the contradictions of modernity: the desire to both separate and reconcile the internal and external, subject and object, cause and effect. He couches the act of photography as an extension of an act of being.

The images in The Decisive Moment reveal two parallel, intertwined threads. One is of the photographer’s way of seeing and how it shifted over time from constructions driven significantly by a 1930s modernist formalism to an increasingly journalistic engagement with his subjects. The other is of the subjects on which he directs his attention. The first half, the “Occidental” work, of Europe and the Americas, is his earlier work, from 1932-1947, and more overtly lyrical while the later, “Oriental” work, made in Asia and the Middle East, is more obviously reportage; roughly this divide reflects his time before and then with Magnum. Vision begets knowledge, even as authorship conveys authority.

The Decisive Moment begins in Europe before the Second World War, delighting in every day life, finding grace in small places, then moves to Mexico, then to the United States after the war, after Cartier-Bresson had escaped from a Nazi POW camp. These pictures show the familiar as unfamiliar: cities feel haphazard, the energy of life at street level at odds with the glamour promised by architecture. It’s all looks and gazes, and the moments are decidedly brief, very much “on the fly”. Over time the images are less overtly geometric though still impeccably composed, and more layered in meanings and gestures. A portrait of a woman on Cape Cod wrapped in an American flag on the 4th of July does not anticipate the moment before or after it; it is a portrait outside of time, but in its accumulation of tiny gestures, feels as an absolutely unique instant.

The second half of the book explores China, India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, Iran and Egypt, places that had been colonial subjects to European countries, that had transformed quickly into actors in a new geopolitical arrangement following the Second World War. Cartier-Bresson surveys the street where modern nationhood is established, in all parts of the world. While some images are historically momentous, such as Nehru’s announcement of Gandhi’s death, most of the pictures embrace the mundane. Some of the pictures are of crowds, but most are of individuals, sometimes responding to the photographer as they go about their business. The pictures feel spacious, the subjects comfortably positioned in their environments. To his Western audiences, he reported on a rapidly changing world, making the unfamiliar familiar; the pictures are at once exotic and quotidian.

***

The Decisive Moment was originally published in the United States by Simon and Schuster in 1952, and simultaneously published in France by Verve as Images à la Sauvette (“images on the fly”, or “images on the run”). The book was reissued last year by Steidl, in both French and English editions. Surprisingly, while Cartier-Bresson’s introductory essay has been available in several photography readers, the book itself, widely regarded as a classic, never saw a second printing from Simon and Schuster.

Sunday on the banks of the Marne, 1938 © The Decisive Moment by Henri Cariter-Bresson, published by Steidl www.steidl.de

Steidl’s beautiful reissue of The Decisive Moment is well-executed, a faithful facsimile of the original in every respect. The slipcase includes the original oversized book with its essay by HCB and a brief “technical essay” by Richard Simon. The reissue also includes a valuable supplemental booklet featuring an essay, “A Bible for Photographers” by Clément Chéroux, rich with information, tracing the history of the book and of many of the ideas in the introduction.

Chéroux provides abundant context for interpreting the book. He discusses Cartier-Bresson’s self-identification through his life, first as an artist and then as a photojournalist, and then again as an artist. He examines the location of The Decisive Moment among these shifts. He describes Cartier-Bresson’s shifts from “I” to “We” and back to“I” as he moves from personal introduction to the more technical body of the essay to return to more personal concluding reflections on photography. He discusses how the book is constructed and printed, and how it was received.

Chéroux also points at ways in which the differences between the French and American versions are revealing. The more technical “The Decisive Moment” contrasts against the more poetic “Images à la Sauvette”. Chéroux shares a list of forty-five possible French titles for the book – images à la sauvette (“images on the fly” or “images on the run”) is the second on the list, Cartier-Bresson’s first title being “à pas de loup”, or “tip-toeing”. The first two sentences in the French and English versions of the essay are inverted, the French beginning with a sentence about the photographer’s early interest in painting, the American one with one about his interest in photography. The English title was drawn from the translation of a French quote by Jean-Francois Paul de Gondi, Cardinal de Retz. The Cardinal, Chéroux explains, used the term “to describe a diplomatic situation particularly opportune for decision-making or action”.

Today the “decisive moment” occupies a unique position in photography. The concept, as it has been construed and adopted, has informed an often positivistic faith in straight photography. At its most useful it’s a recognition of the photographer’s subjective act of witnessing, the basis of documentary photography and photojournalism. This form of straight photography falls in and out of favor in fine art photography contexts, partly because it is so resolutely modern in its notions of visibility and the forms of truth on which it relies, and which it professes to verify.

But it’s Cartier-Bresson’s humility – his insistence on respect for both subject and self – that could also serve as a powerful guide for both photographers and their audiences. Cartier-Bresson’s photograph is only as good a document as its author was occupied by and aware of the moment at its making. This dynamic accounts for the “timeless” quality of the images, the feeling that everything – form, mood, and the connection between subject and photographer - is in balance. The reality is that this balance was ever a dynamic equilibrium, accomplished by the photographer, not by the world that he photographed. The book is not only a collection of images but also a continuity of assessments and statements.

Leo Hsu is a photographer and writer based in Toronto and Pittsburgh.

Contact Leo here.

Support Fraction and purchase The Decisive Moment here, or Images á la Sauvette here.