The Big Picture: A Transformative gift from the hall family foundation

Creating a transformative experience at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

April 28 – October 7, 2018

Review by Lauren Greenwald

Issue 116

This September, a series of fortunate events brought me to Kansas City, MO. I had a few hours free before my flight home, so I decided to spend them at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. I set off into the rainy morning with few expectations but to spend a pleasant few hours, and there was a promising looking photography show on view. This all changed when I arrived at the museum. I teach art for a living, and I am particularly concerned with the state of art education today. I recently had a long conversation with a friend in which they asserted that art museums are elitist institutions and alienate the majority of the public. But when I walked in the Nelson-Atkins that day, I noticed something different from some of my recent visits to museums. First of all, admission was free. Second, everyone, from the greeters to the charming coat check gentleman (whose station faces a gigantic tapestry-like sculpture by the artist El Anatsui), was smiling, friendly, and engaged. There was ownership there – rather than hourly employees marking time, every person I met seemed deeply invested in the institution. Even the guards in the galleries were animated – not a blank face in the bunch. By the time I reached the exhibition space, I was in a pretty good mood. By the time I left, I was elated. The depth and breadth of the work was stunning. A nicely comprehensive survey of the history of the medium, it included many of the well-known works which appear in every photo survey (Diane Arbus’ Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, NYC, for example) but with so, so many other surprising examples. An elegant, spare composition depicting cavalry in a field by Gustave Le Gray was one of the first things I noticed, a remarkably contemporary landscape for a salt print from 1857. A slightly creepy self-portrait by Claude Cahun pulled me away from the 19th century works on display towards a larger, brighter exhibition space, passing by an amazing Thomas Demand print (one I had never seen before) and other delights on the way, such as a perplexing but engaging image of a stuffed bear by the artist Patti Smith. And in the latter portion of the exhibit, several works explored the malleability of the photographic object, including a fantastic artist’s book mixed-media piece by Keith Smith and, anchoring the room, Dayanita Singh’s Kochi Pillar, a sculptural “mobile museum.”

Camille Dolard, French (1810–1884). Self-portrait as a hookah smoker, 1845. Daguerreotype, 8 1/2 × 6 1/2 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2017.44.5.

I wanted to know more about the making of the exhibition, so one morning recently I spoke to Associate Curator Jane Aspinwall about The Big Picture and the remarkable relationship between the photography department of The Nelson-Atkins Museum and the Hall Family Foundation. The full title of the exhibition was The Big Picture: A Transformative Gift from the Hall Family Foundation, and the transformative gift refers to a $10 million gift for photography acquisitions between 2015 and 2018.

Hallmark Cards, Inc. and the Hall Family Foundation have been for many years and remain strong patrons of the arts, particulalry in and around Kansas City. The Hallmark Photographic Collection (HPC) was for many years part of Hallmark corporate holdings, and the only way to see the collection was by appointment, or through one of the special exhibitions organized with the Nelson-Atkins or a traveling exhibition. When Jane Aspinwall was a graduate student in art history, she had the opportunity to tour the collection, and she had what she calls a “transformative art moment” when she saw a daguerreotype for the first time. She had been studying American painting, but after this, she shifted her focus to photography. She began working as a researcher with the HPC in 1999, before moving on to her first large curatorial project with Hallmark and the Nelson-Atkins in 2004, researching the book and co-curating the 2007 exhibition Developing Greatness: Origins of American Photography, 1839-1885.

In 2005, the collection was gifted to the Nelson-Atkins, and she, along with curator Keith F. Davis, became part of the new Photography Department. At this point, the Nelson-Atkins held only about 1,000 photographs with no curator of photography, and the HPC collection added around 6,500 pieces, primarily American in scope. Fortunately, a new addition to the museum, the Bloch Building had just been completed, allocating 3,000 square feet of permanent galleries for photographic exhibitions. The Hall Family Foundation continued to fund the Photography Department, and under their patronage the collection doubled in size from 2007 to 2017. 19th Century European work, in particular, was added to the collection, with a significant increase in daguerreotype holdings. While historical holdings have always been important to the collection, the curatorial team worked to acquire bodies of work in depth as a way to stage future exhibitions. At any given time, 1,000 sf of the gallery space are dedicated to a rotation of historical holdings, with the remaining 2,000 sf for the smaller more specialized shows. One, from 2012-2013, was titled Cabinet of Curiosities: Photography & Specimens and examined the relationship between art, science, and photography, which included early x-rays, telescopic images, and unusual artifacts, like pulled teeth from the collection of Peter the Great.

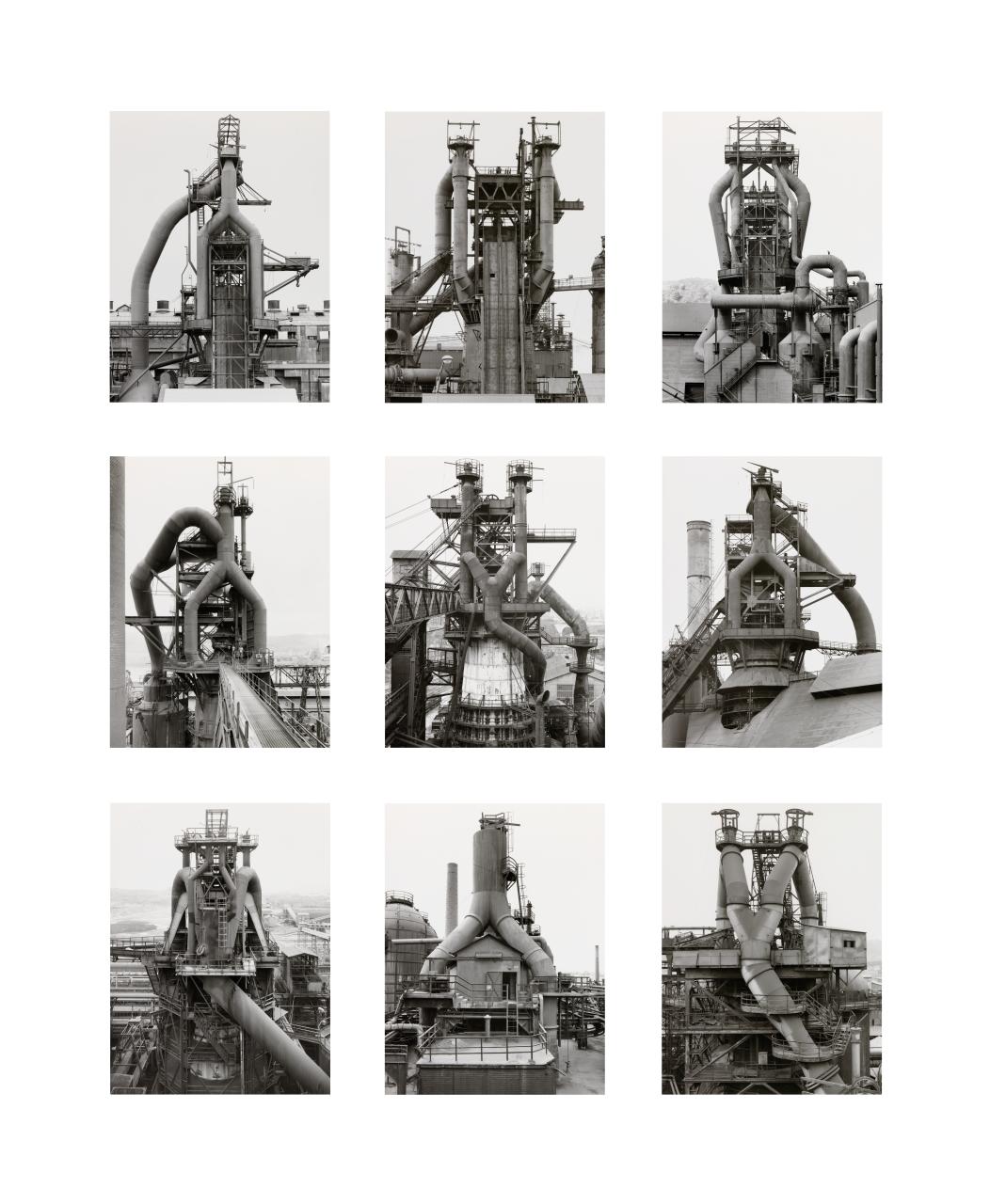

As Aspinwall was telling me about this history, I was more than a little amazed at this level of patronage. And I confess to wondering whether there were ever any attempts to influence or censor the collection. But apparently, this is not the case, and the Foundation has been scrupulous over the years in giving the curatorial team and the museum complete autonomy over acquisitions. Then, in 2015, they were informed of the $10 million gift, for the purposes of expanding the collection over the next two years. At this point, in the view of the curators, the collection was lacking European modernism, conceptualism from the 1960s & 1970s, and key Contemporary (read costly) pieces. They were able to diversify and strengthen their international holdings – for example, they were had a Becher grid, now they have two. The end of the purchase initiative was celebrated by a target exhibition to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the Hall Family Foundation itself.

In all, 835 pieces were purchased, 99 of which were included in The Big Picture. In curating the show, all three photography curators, Keith Davis, April Watson, and Jane Aspinwall, voted on what to include. They ended up agreeing unanimously on over 65% of the items, and everything in the show was agreed upon by two of the three curators, but they continued to acquire works right up until the installation. According to Aspinwall, “because of the nature of the acquisition process, we weren’t able to include some pretty terrific works in the exhibition…the difficulty was more in what was left out.” One prized purchase was a self-portrait by the French painter/photographer Camille Dolard – in all, he made 3 self-portraits: one (in the exhibition) titled Self-Portrait as Hookah Smoker. After purchasing that piece, they found and acquired another, but not soon enough to include in the exhibition.

The Big Picture ended up being well visited with national recognition, but Aspinwall noted that this is the first of a long series of ambitious exhibitions to come. Programming is already confirmed up until mid-2020. Upcoming shows include: Structured Vision: The Photographs of Ralston Crawford, Anthony Hernandez: LA Landscapes, and an exhibition of the Alfred Eisenstaedt portfolio. In describing this project, she explained, “Alfred Eisenstaedt was a Jewish freelance photojournalist. Oppression in Hitler’s Nazi Germany caused his immigration to the United States in 1935. Eisenstaedt chose 90 photographs, which he packed in a suitcase, to bring with him. Although the portfolio includes some iconic images, the real value is that they are his personal selection, representing his formative work in Europe. I don’t know what criteria he used to select his images—there is a mix of political, celebrity, fashion, and international subject matter. I am fascinated by the story and that the photographs serve as a time capsule of such a formative moment in German history.”

In the brochure for The Big Picture, it is noted that the photography program wants “to be clearly recognized as the key program–the leading research resource, source of scholarly insight and innovation, and center of public interest–in the entire region between Chicago, Houston, and the West Coast.” They certainly seem poised to do so, not only in research, but in access and education. The educational programming at the Nelson-Atkins is impressive; there is a dedicated educator center, and they create teacher guides for many of the photography exhibitions. This allows teachers to bring their students and to teach at their own pace, without requiring a docent to lead the group. And while the museum is closed to the public on Mondays and Tuesdays, it is open to school groups on Tuesdays. Accessibility is a primary goal of the museum, and there are many special programs, such as tours for mothers with children in strollers. Much of this has been credited to the leadership of the current CEO and Director of the museum, Julián Zugazagoitia, who is committed to building community. He has expanded the museum’s loan program, partnered with local institutions, and sponsored a wide variety of public initiatives such as the Deaf Culture Project. The goal, says Aspinwall, is to foster an “open meeting place where people can have transformative art experiences.”

This word, transformative, keeps coming up. And I think it’s particularly appropriate here. An exceptional patronage fostered a transformative gift. It’s a rare and wonderful thing to be able to go to a space dedicated to the arts on a regular basis, especially one in which everyone, even the most casual visitor, is made to feel completely welcome and at home – as if it belongs to you. The people of Kansas City have that, and I admit I’m a little jealous. As long as the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and their Photography Department have anything to say about it, visitors will keep having those transformative experiences.

Pierre-Louis Pierson, French (1822–1913). The Countess de Castiglione, ca. 1856–57. Hand colored salt print, 10 11/16 × 10 inches. The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2015.67.44.

Gustave Le Gray, French (1820–1884). Cavalry maneuvers, Camp de Châlons, 1857. Albumen print, 10 3/16 × 13 1/8 inches. The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2017.61.20.

Claude Cahun, French (1894–1954). Self-portrait, 1927. Gelatin silver print, 4 1/8 × 3 1/8 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016.75.26.

Bernd & Hilla Becher, German: Bernd Becher (1931–2007), Hilla Becher (1934–2015). Blast Furnace, Frontal Views, 1979–86. Gelatin silver prints (printed before 1987), 60 3/8 × 48 3/8 × 1 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016.75.13.1–9.

Carrie Mae Weems, American (born 1953). A Place for Him, A Place for Her, 1993. Gelatin silver prints with text, each 20 × 20 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016.75.357.1–4.

Dayanita Singh, Indian (born 1961). Kochi Pillar, 2015. Mixed media with inkjet prints, 89 5/8 × 22 × 21 3/4 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016.75.266.1–34.

Thomas Demand, German (b. 1964). Vault, 2012. Chromogenic print, 86 3/4 × 109 1/16 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2017.61.9.

Patti Smith, American (b. 1946). Tolstoy's Bear, Moscow, 2016. Inkjet print with pencil, 7 7/16 × 5 3/4 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016.51.5.

Installation View, The Big Picture. Courtesy of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Installation View, The Big Picture. Courtesy of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

Lauren Greenwald lives and works in southern California. She teaches photography at MiraCosta College in Oceanside, CA.